Remembering Internet Explorer, the now-dead browser that once powered the Internet

Microsoft Internet Explorer has died many times over the years, but today matters. The final version of the browser, Internet Explorer 11, will no longer receive support or security updates starting today, and will be phased out from Windows 10 PCs at some point in the future via Windows Update. It was never installed on a Windows 11 PC at all.

Microsoft says people who open Internet Explorer “over the next few months”will be “gradually”redirected to Microsoft Edge instead, which will offer to import all bookmarks and saved passwords to make the transition easier. For users and businesses that need Internet Explorer to access individual websites, Microsoft will continue to support IE mode in Microsoft Edge until at least 2029. IE Mode combines the Edge UI with the old Trident IE11 rendering engine, allowing older websites that don’t display correctly in newer browsers to continue working.

This is the end of the road for Internet Explorer, the browser that wiped out all competitors in the browser wars of the late 90s only to be completely wiped out in the browser wars of the early 2010s. For those who haven’t been there, we’ve put together a brief history of the life and times of Internet Explorer. The heyday of IE is a thing of the past, but it’s worth knowing the whole story. Google Chrome is leading the world today, but it didn’t happen overnight and the browser wars were cyclical.

From Mosaic clone to world eater

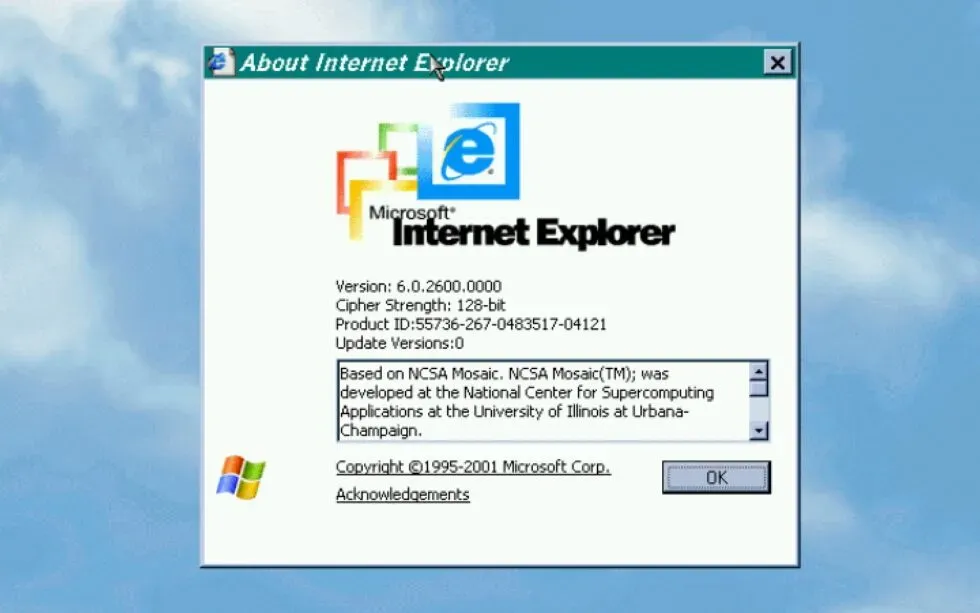

The history of Internet Explorer begins with NCSA Mosaic, one of the first graphical web browsers. Several projects preceded it – Tim Berners-Lee’s Nexus is generally considered the first browser, and Cello preceded Mosaic on the Windows PC – but Mosaic popularized browsers as we know them, with a recognizable modern user interface and support for embedded images. The ability to combine images and text on the same page may seem like the bare minimum for a browser today, but in the early 90s it was a revolution.

Mosaic inspired competitors. Some of these, such as Netscape Navigator, were separate projects, although many of the people who created Netscape worked on Mosaic first. Others were direct offshoots of Mosaic and used its trademarks and source code. One such offshoot was Internet Explorer.

Microsoft licensed a version of Mosaic from Spyglass, Inc., which itself licensed the original version of Mosaic in order to unify its disparate codebases and ensure that the browser supports the same functionality on all supported platforms. Microsoft was just one of the companies that licensed the Spyglass version of Mosaic; companies hoped to break into the browser market quickly by putting their name on an existing browser rather than building one from scratch.

The first few versions of IE didn’t get much attention, and they basically caught up with Netscape by adding support for more platforms (by the time version 3.0 came out in mid-1996, IE ran Windows 95, NT, and 3.1, as well as Mac 68K and PowerPC). But at the time, Windows 95 was taking over the computing world, and Microsoft used its growing dominance in the PC world to promote its other products, most notably IE.

The integration of Microsoft Internet Explorer with Windows, and by the time Windows 98 and Internet Explorer 4 arrived, even deeper integration of the browser into the rest of the operating system, was a double-edged sword. On the one hand, IE’s market share skyrocketed in 1996 and 1997, robbing Netscape of a huge share simply because it was available on most Windows 95-era PCs. On the other hand, it got a lot of legal attention, starting with the Spyglass settlement. $8 million (Microsoft agreed to pay royalties to Spyglass based on IE sales, and then bundled it with Windows for free, technically no revenue) and continued with a landmark event. antitrust case filed by the US government.

Unless you’ve lived through that era, it’s hard to imagine just how much computing power Windows had in the late 90s. The Mac existed and was still loved by the proverbial “lunatics”, but it was at its peak in terms of market reach and cultural significance. Early Windows competitors such as OS/2 and BeOS were largely defeated. We’ve gone years from Linux distributions that even claimed to be user-friendly. Palm Pilots, Apple Newtons, and Pocket PCs were weird niche gadgets used by business dads, guys who learned valuable lessons from ’90s movies about putting family over work.

Leave a Reply